Graffiti, tags, murals, stenciling, paste-ups… street art is a diverse artform with many subcategories and styles. While some might deride the practice under the blanket term of vandalism, for proponents of the artform, taking art out of the gallery and into the streets is about civil disobedience, ownership of space, and creative expression outside of the mainstream. We dip into the origins of graffiti in NYC and speak to artist Richie ‘Pops’ Baker about how the medium came to Nottingham in the 1980s…

Nottingham is often referred to as ‘a city of rebels’, where writers, activists and outliers have gone against the grain, pushing against the boundaries set by the establishment. It could be said that leaving one’s mark, with a message of ‘we live here’, is a tradition that goes back millennia in Nottinghamshire.

At the tip of the county, Creswell Crags boasts the oldest verified cave art in northern Europe, discovered by archaeologists in 2003, and dating back 12,800 years, with depictions of red stags, birds and humans. Over eight hundred caves sit under the city centre and were hand carved into the sandstone, often by the poorer classes, altering the topography of the city and providing space in a crowded urban landscape. And, in the early 19th century, the Luddites took direct action against the machine industry by smashing the stocking frames which threatened their livelihoods. As such, is there a more fitting place than Nottingham for people to make themselves known through graffiti?

Well, perhaps before we get into all that, we should take a journey to New York, where the story of graffiti began. It’s the end of the 1960s; punk and hip hop are yet to emerge, Andy Warhol is challenging tradition by making mass-produced Pop Art about celebrity and consumerism. In the streets, subcultures are beginning to make their mark through fusing art, music and fashion.

In the cities of Philadelphia and New York, names begin appearing on walls scrawled in paint; Cornbread, Cool Earl, and Julio 204. These simple tags, often made with markers or car spray paint, gain notoriety, inspiring other young would-be artists. In 1971, the phenomenon hits the mainstream with a New York Times article 'Taki 183' Spawns Pen Pals - a story about a seventeen-year-old from Washington Heights who marked his name (and street number) everywhere from New Jersey to Connecticut.

That same year, the first ‘piece’ (short for masterpiece) was on a subway train painted by Super Kool 223. Choosing a wider spray nozzle, he was not only able to make a more detailed tag in less time, but as his canvas travelled from district to district, the popularity of his work, and the artform in general, blew up. Writer crews formed in different neighbourhoods, and a sense of competition grew to make larger, more stylised, and pictorial works. The artist had left the studio, and the street was where it was at.

But there was more to the mischief and artistry of this early graffiti. The Civil Rights movement had ended in 1968, yet racism and inequality remained rampant, and bubbling beneath the letters and lifestyle, the politics of the time was steering young creative people to make their voices heard. Hip Hop as a cultural movement was emerging, mainly originating in the Bronx, with graffiti writing sitting alongside breakdancing, MCing, turntablism, and ‘knowledge of the self’ as one of its five pillars. Much more than a mere musical genre, Hip Hop provided a means to celebrate, understand, express and confront aspects of the world, notably from a Black perspective. As a form of protest channelled through art, it quickly became one of the coolest and most innovative movements around – gradually getting picked up by more mainstream artists.

The artist had left the studio, and the street was where it was at

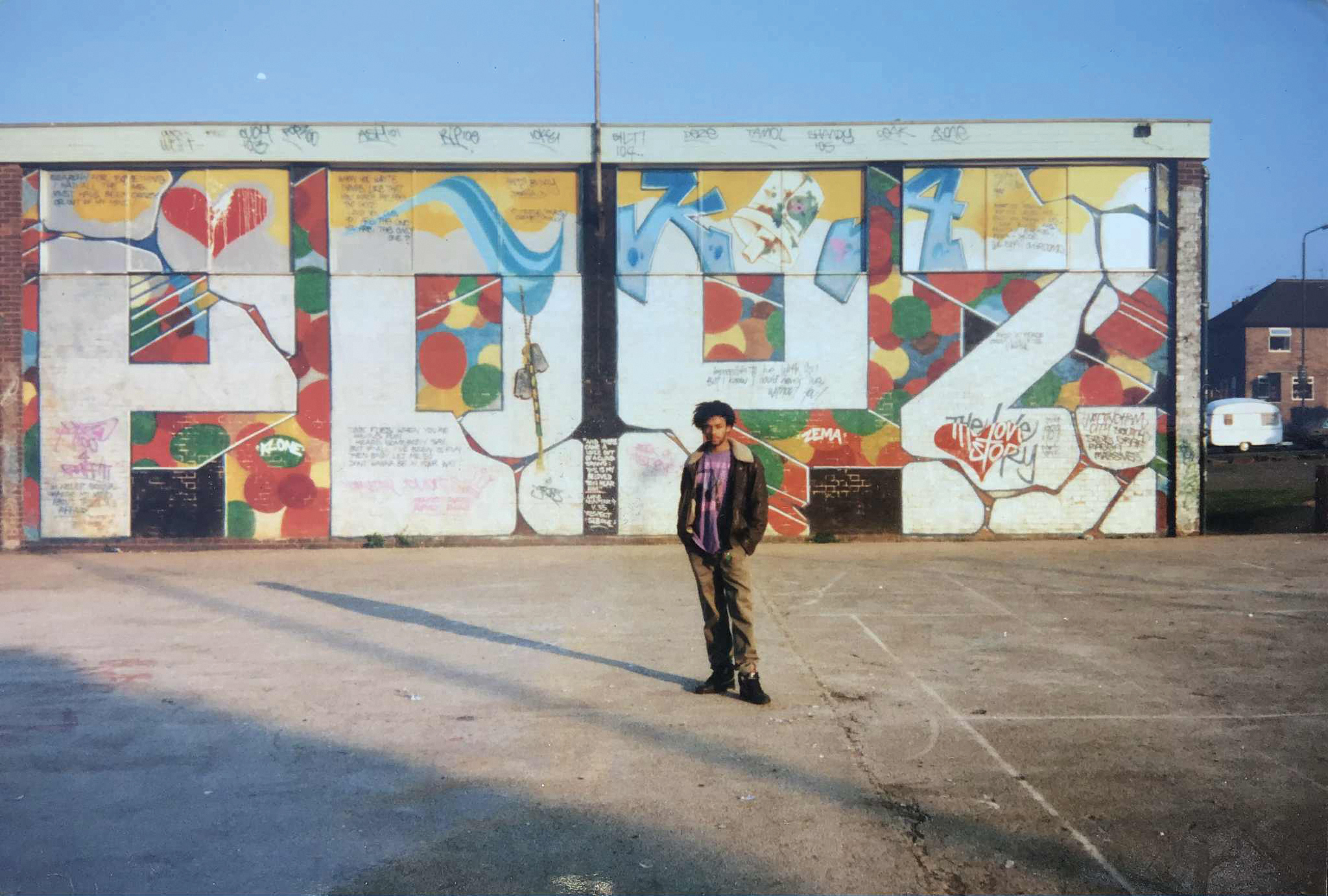

But how did this very localised subculture make its way from the cultural boiling pot of NYC to an East Midlands city hundreds of miles away? To find out, I spoke to Richie ‘Pops’ Baker, an influential artist in the early Nottingham street art scene who painted over three hundred pieces around the city between 1985 and 1992.

Born into a mixed-race family, Pops grew up in Clifton during the 1970s on the biggest council housing estate in Europe. He describes his experience of everyday racism as inspiring a “fertile field of potential service toward my fellow human family”, and choosing visual art as his medium, his body of work has evolved with a thread of love, empathy and positivity throughout the years. A significant piece that many may remember is the Stop Wars wall, which sat at the intersection of Goose Gate and Cranbrook street. A work by Pops which he has recreated several times, the concept was dreamt up by his partner, and was later evolved into a new work: Start Peace.

During the early 80s, Pops describes himself as a young Mod who was fully resisting “this thing called Hip Hop.” Although the graff scene had been blossoming over the pond for over a decade, the slow moving culture in the pre-digital world meant Pops and others in Notts were only “privy to the odd visual gem on our screens.” He recollects seeing the character Rembrandt in The Warriors painting a red ‘W’ on a wall, and an appearance by American artist Dondi spray-painting in the background of Malcolm McClaren’s Buffalo Girls on Top of the Pops in 1982.

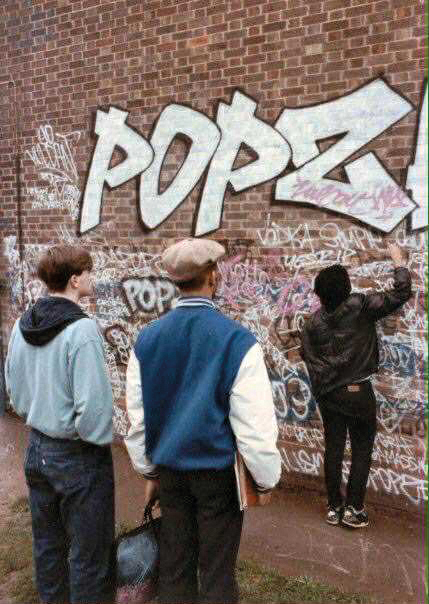

However, it was the film Style Wars, a 1983 documentary focusing on graffiti art and breakdancing, that would truly change things. “It was totally game on,” Pops explains. “By 1985, [in Nottingham] we were all pretty much still at the humble beginnings of properly catching up as best we could according to our own unique set of inner and outer circumstances, in terms of making a real art and a lifestyle of it.”

“Pre and post Style Wars, some of our first local Clifton ‘taggers’ emerged with names like Snake, Mr Flash, Slix, Fizz, Rike, Dooby D, Zoro, Skooby D, Zeroe, and me… Popsi P,” he explains. “And the first ‘writers’ we found from elsewhere in the city went by names like Tat2, Tiny T, Mad, Craze, Rip, Deze, Brains and Ribs, etc.”

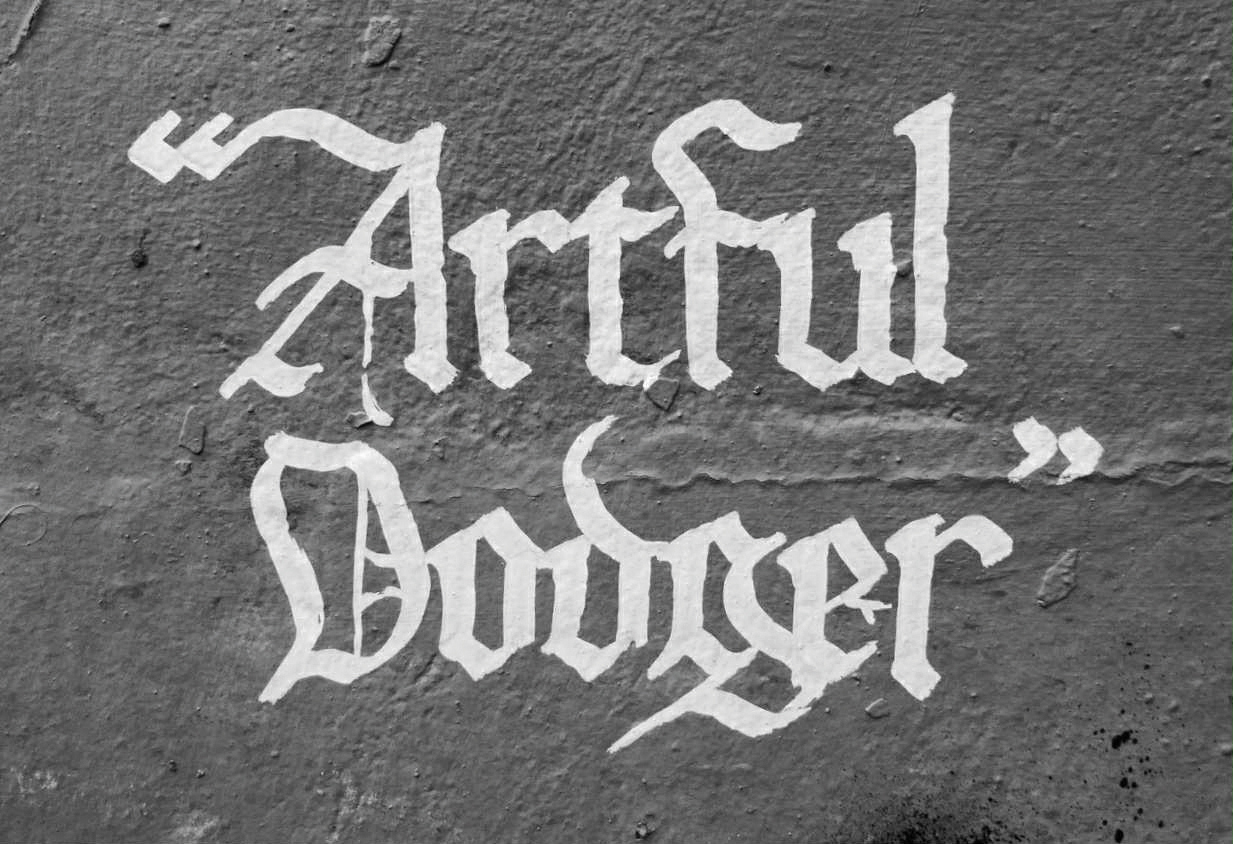

But for Pops, one name stands out above the rest - the infamous ‘Artful Dodger’. “He notably neatly wrote his name in Old English italics on the front of Nottingham Station, on one of the pillars in the Market square, and on the insides of at least a couple of the buses,” says Pops. But it was not just the “dynamic and tragic Charles Dickens character where our own local outlaw got the name,” or the “carefully written traditional Olde English font reproduction,” that made the Artful Dodger’s work catch his eye. Even before Style Wars, as a teen, Pops had caught sight of an advert Dodger had created for Weetabix - a most unusual collaboration for the time considering there was still felonious work from Artful up in the streets.

“A big printed graffiti style billboard poster appeared on the wall in Broadie bus station. Legally, and signed ‘Artful’. But not in the usual old English font this time. So I was confused, and amazed, and somewhat inspired,” he recalls. “That was enough to get my curiosity cogs rapidly spinning.”

Over the years Pops’ relationship with street art has naturally ebbed and flowed. After eight arrests for vandalism he decided to quit in 1992, almost entirely due to concerns about the CFCs in the spray paint and their damaging effects on the ozone layer. “But it was also partly due to the criminal aspects of it and how that could also influence the younger generations being born and growing up around me,” he says. “And therefore about my own and other people’s mental, emotional and physical health in relation to the whole lifestyle we’d developed over those years.”

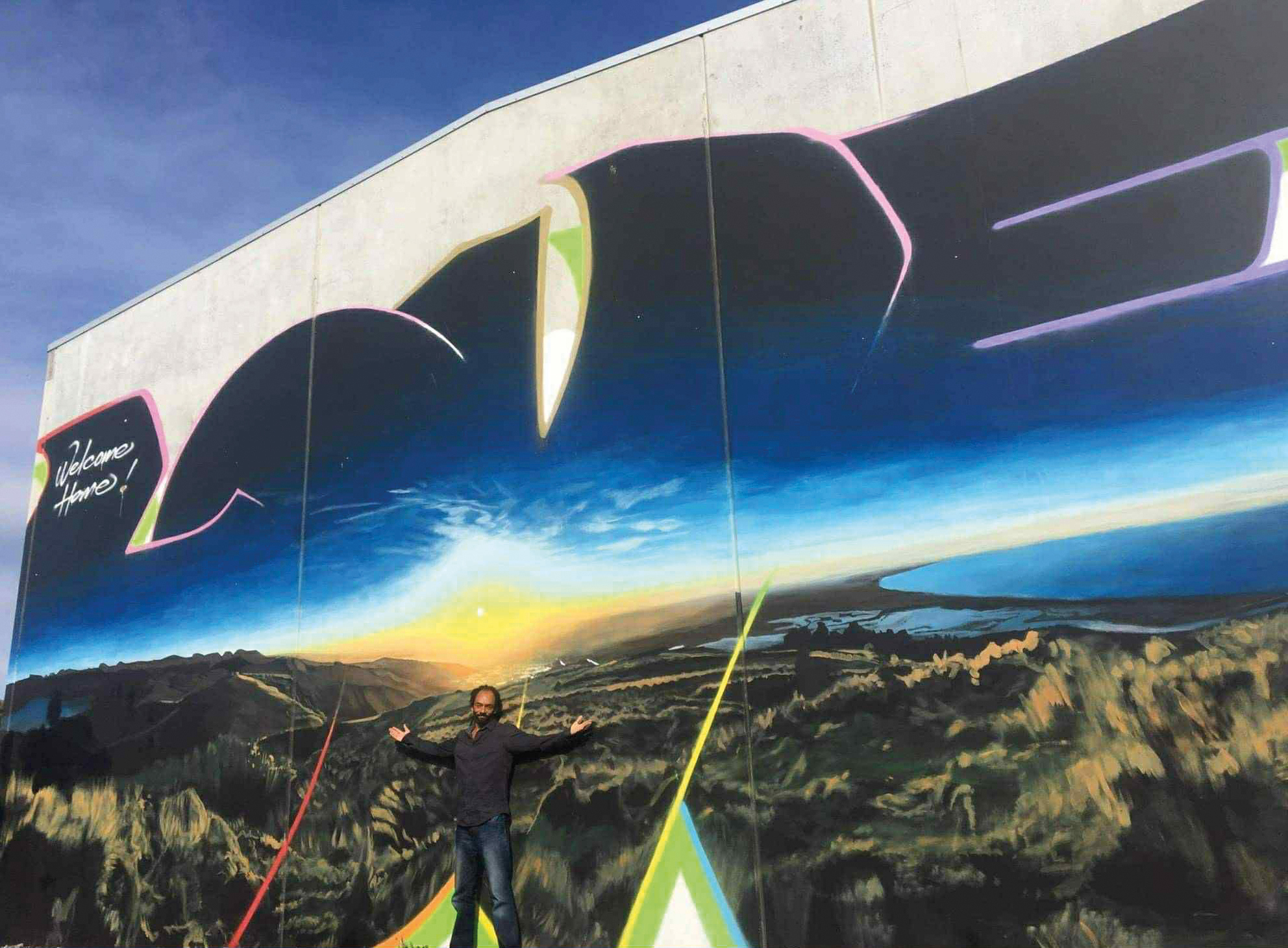

Now living in New Zealand with his family, he describes one of his favourite graffiti-related stories happening in 2004, while he was watching a TV show about Hip Hop on a new Māori channel. The introduction of a channel completely managed by Aotearoa/New Zealand’s indigenous culture was not lost on Pops: “Thirty or so years prior, lots of them were beaten in schools just for speaking their own language… The language of their own thoughts. So having their own channel to do whatever they wanted with now was very much a big deal.”

“Due to the strains of struggling as new parents, experiencing a lack of sleep, etc., I found myself experiencing a strong sense of ‘Come on life, I need a little self esteem boost… help me out here...’” he says. “They get onto talking specifically about graffiti, how it took off in New York on the trains and then spread around the world. When they mentioned it going to Europe, they actually showed a photo of my Popz 100 train - my 100th piece. The painting I got my name from that I’m largely known for on the graffiti scene. I was tripping! Here on the almost exact opposite side of the little/big planet and my prayer for an ego boost was synchronistically, miraculously, directly answered.”

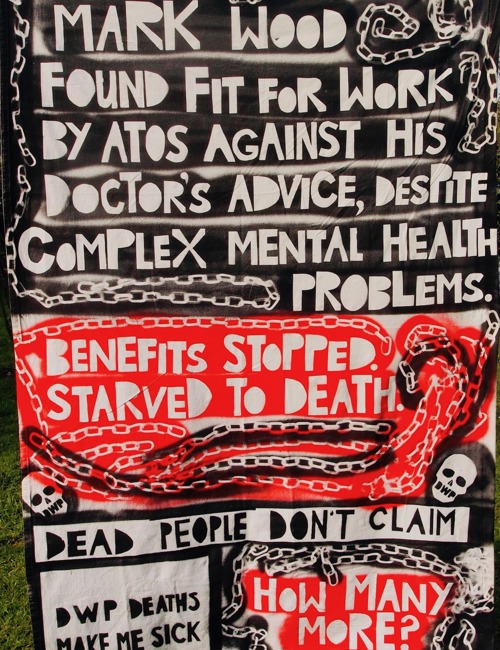

Today much of our towns and cities are infiltrated by images and signs we have little say in; billboards blaring about things we should buy, drab signage warning about rule-breaking, or oligarch owned media telling us what we should think.

Of course, with graffiti, a little consideration for which wall, building or other piece of street furniture one paints on is vital - but as a lover of strange little messages placed around our streets, part of the attraction is the mystery, the synchronicity, and the sense of connection that comes with stumbling upon the mark of a stranger who has passed by, saying ‘I was here’. And somehow we begin to know their prints, like familiar faces.

There are a dozen tangents one could go down when talking about graffiti - the respect of unwritten rules within the culture, the names that pushed the movement forward, questions of legality, what is regarded as high versus low art, right down to the council’s cleaning costs - so take this article as a brief toe dip, with a much romanticised conclusion… But don’t forget to ask - whose streets are they anyway?

We have a favour to ask

LeftLion is Nottingham’s meeting point for information about what’s going on in our city, from the established organisations to the grassroots. We want to keep what we do free to all to access, but increasingly we are relying on revenue from our readers to continue. Can you spare a few quid each month to support us?